Math Modeling Mindset and an Orange Juice Machine

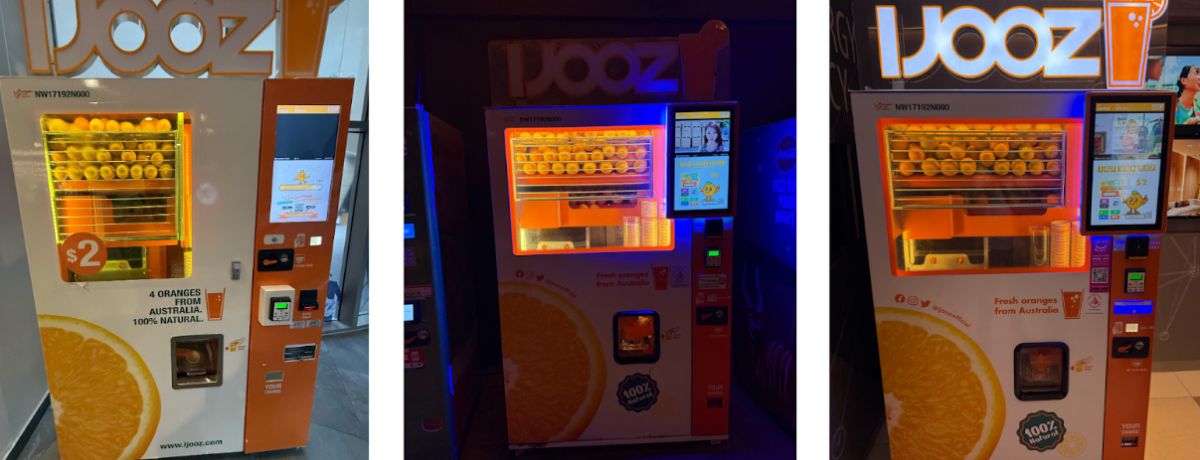

A few months ago, I had the opportunity to travel to Singapore. I arrived early in the morning, a day ahead of my meetings. After a long day of flying, wandering the city, and battling jet lag, I gave in to curiosity and thirst. I stopped at one of the bright, spotless vending machines I’d been passing all day.

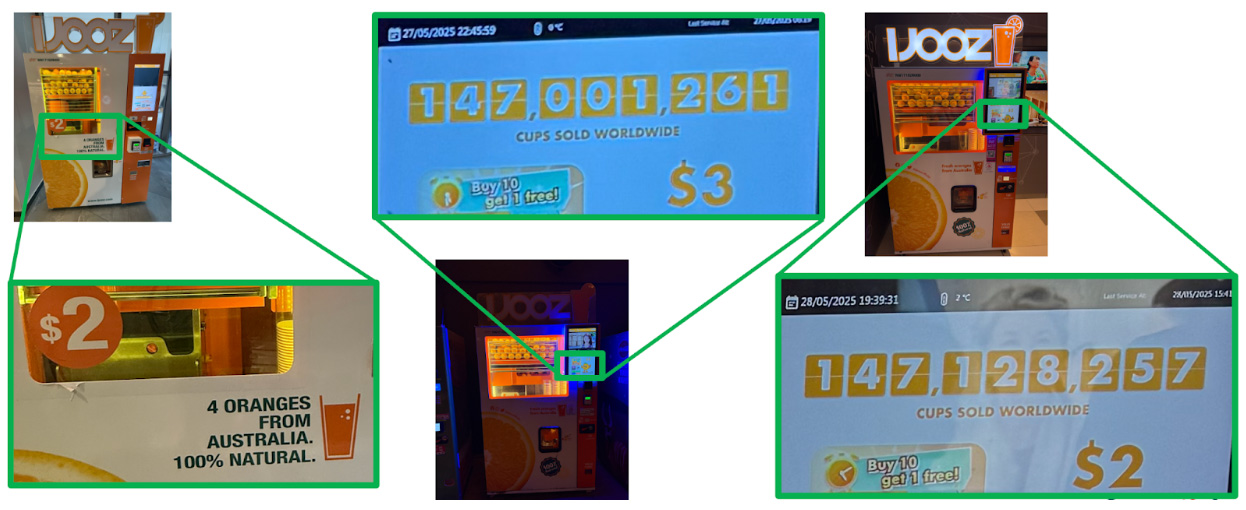

These machines juiced fresh oranges right in front of you. Oranges dropped, squeezed, and poured into a cup in under a minute. I expected to notice the juice (it was good!), but what really caught my attention was the screen. It displayed a global running total of cups sold: 147,001,261. It reminded me of those airport water bottle refill stations that display how many bottles have been “saved” by refilling. The screen also showed the internal temperature and where the oranges came from (Australia).

From Curiosity to Calculation

That number was impressive—and it made me wonder: How much juice gets sold in a day? Or in an hour?

The machines didn’t show sales for each location (as far as I could tell) only a global total. But I could still get a rough idea by checking the counter at different times. The next day, I found another machine while visiting the zoo. The total had jumped enough for me to estimate roughly 6,050 cups had been sold per hour over the last 21 hours.

Nearly a day later, I checked again—this time at a third machine—and was surprised to find the rate had dropped to about 3,450 cups per hour. What a shift!

Questions That Followed

At that point, I was hooked. How many cups are sold per machine? Which locations are the busiest? Do certain days, or certain conditions like temperature, impact sales? How many machines are there worldwide, and where are they located? (As an Australian colleague shared with me, even though the oranges are sourced from her country, she’s never seen one of the machines.)

The display also revealed that each serving used four oranges. That made me wonder:

- Why was the zoo machine charging $3 a cup while others charged $2?

- Was it because the zoo machine was outdoors while the others I’d seen were inside?

- How much does fresh-squeezed orange juice cost elsewhere, or to make at home?

- Is this an environmentally sustainable way to get juice? What’s the environmental “cost”?

- How are the oranges transported?

These weren’t just idle thoughts; they were potential variables that if identified, could help me understand the iJooz “phenomenon.” I didn’t have a single, clear question to model (unless you count “Should I open my own mobile juice company?”), but I was already using math to explore the world around me.

Opening Moves in Modeling

I didn’t have enough information to “finish” the model, in fact, I didn’t even have a specific question in mind, and that was fine. In life and modeling, you very rarely start with all the facts required to “complete” a process, and in many cases, you. The process begins with observation, quick calculations, imagining what else you’d need to know, and following where the next question leads.

It’s not about having perfect, per-machine numbers on a screen. It’s about recognizing that opportunities to use modeling to understand the world are everywhere. So next time something catches your eye, imagine what you’d want to know, what might affect it, and how you’d begin. You might not get to an answer right away, but you’ll be doing the most important part: starting.

An Invitation to Notice More

This juice machine is just one small example, but it’s the same process I see in classrooms, competitions, and conversations around the world:

- You pause.

- You ask a question.

- You make an opening move.

This is the first in what I hope will be a regular series of “Math Modeling Mindset” posts—short stories from everyday life that show how curiosity can lead to mathematical thinking.

So next time something catches your eye, imagine what you’d want to know, what might affect it, and how you’d begin. You might not get to an answer right away, but you’ll be doing the most important part: starting.

Written by

Ben Galluzzo

Ben Galluzzo is a national and international leader in mathematical modeling education with experience in PK–12 and higher education. Before becoming COMAP’s Executive Director, he was Associate Professor of Mathematics at Clarkson University, where he also served as Associate Director of the Institute for STEM Education and Head of The Clarkson School. He has led COMAP’s HiMCM Contest, chaired the International Mathematical Modeling Challenge Expert Panel, and contributed extensively to math modeling contests as an advisor, problem writer, and judge. Ben’s work has helped secure nearly $10 million in external funding, and he is a recipient of the MAA’s Henry L. Alder Award for Distinguished Teaching. He co-authored the GAIMME Report and two of SIAM’s most-downloaded mathematical modeling handbooks.